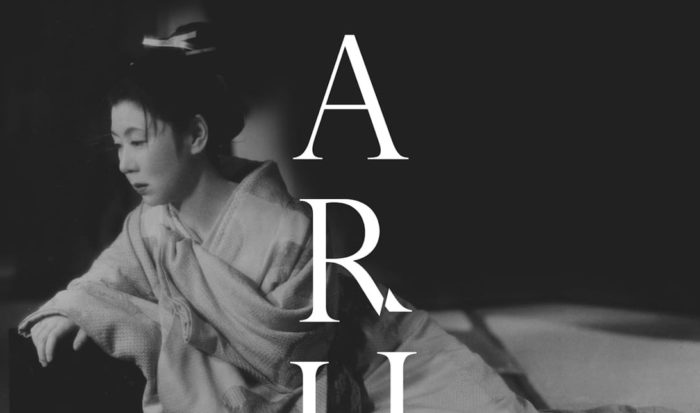

When we recorded the recent podcast where we picked the various films we’d be reviewing for Criterion Month this year, I admitted that I weirdly could not remember if I had seen 1952’s The Life of Oharu. After seeing that this film wasn’t released by Criterion until 2013, I deduced that I probably hadn’t seen this movie, since it seems like I would have watched it either in college or slightly thereafter. Also, after actually watching the film, none of it really felt familiar, and considering how striking the movie’s images are and how singular its sense of anguish is, I probably would have remembered this movie, especially when it features Toshiro Mifune in a non-Kurosawa supporting role. I think this uncertainty derived from the fact that I’d seen two of Kenji Mizoguchi’s slightly later films from this era, 1953’s Ugetsu and 1954’s Sansho the Bailiff, and couldn’t remember much about them, despite thinking they were both borderline masterpieces. While I wouldn’t say The Life of Oharu is quite in that league, it still shows how much of a roll Mizoguchi was on in the years leading up to his death in 1958. Continue reading