I think I’m a huge fan of Charlie Kaufman’s brand of introspective cinema. I certainly love his combination of quirk, genuine weirdness, existential terror he managed to blend into movies like Being John Malkovich, Adaptation., and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. But there was a loftiness to those films that I just felt Anomalisa didn’t have. It’s a question asked knowing no one can answer, more like a poem than the novels I want from Kaufman.

Michael Stone (voiced by David Thewlis, this is a stop motion movie, I should mention) is a man living in isolation. He’s on a trip to Cincinnati to speak at a conference, but can’t work up much enthusiasm about that, nor his ritzy hotel or really anything. So alone is he that it sounds like everyone, literally everyone else in the movie, has exactly the same voice – Tom Noonan. He’s not sure if he’s losing his grip or if there’s a massive conspiracy going on, but Michael’s monotone world is definitely pushing him to his breaking point – until he hears another voice: Lisa (Jennifer Jason Leigh), a woman just down the hall.

There are certain traces of one of my favorite movies, Lost in Translation, in Anomalisa. Both tell the stories of older men, deep into dealing with existential crises, who seek revitalization in a younger woman who is staying in the same hotel. But the crisis of Anomalisa is a nightmarish one, despite it often being played for laughs, Michael is genuinely in a bad place and finding a way out won’t be easy.

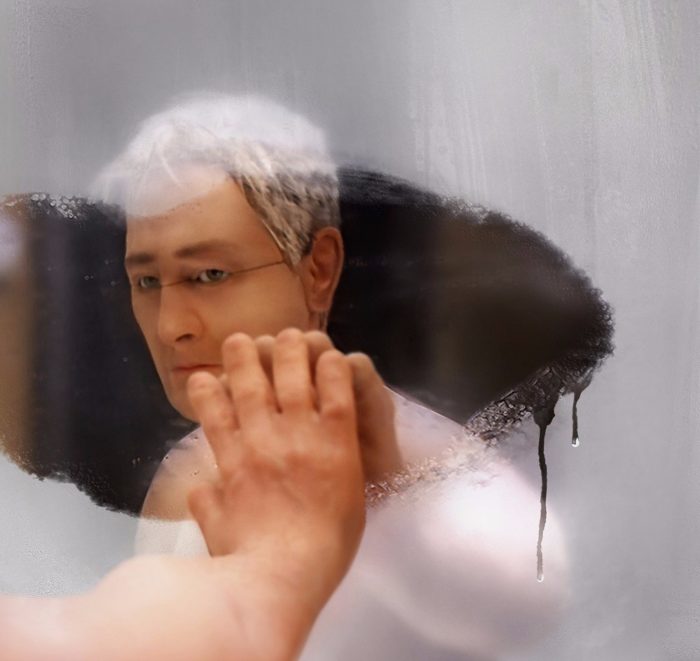

There are so few stop motion movies these days, and even fewer of them have anatomically correct puppets. Anomalisa is a decidedly adult story, steeped in sophisticated ideas that would probably be quite alarming to a child. Does the story of a customer service expert losing the ability to distinguish between people have to be animated? No, but it’s not for you or I to question such things.

After doing so much wonderfully, Anomalisa really left me hanging with its final scenes. It’s easy to guess that just as indignant as I was, just as confused as Michael, so too was Kaufman, who was probably dealing with his own similar problems and trying to address them by making this movie. I guess the great lesson in all this is you must look for answers within, which is something. Not damn near enough.