34th Academy Awards (1962)

Nominations: 12

Wins: 3

Stanley Kramer did not fuck around. Hollywood’s king of “heavy dramas” made sure every time he got to make a movie, it was important (and often set in a courtroom, even if he wasn’t the director). Case in point, Judgment at Nuremberg, a fictionalized version of one of the 12 Nuremberg Military Tribunals that weren’t even popular when they happened. That was 1947, two years after the war, and Americans were more interested in restarting their lives at home than thinking about the past. That goes doubly for the German people, whose immense guilt and shame forced them to claim ignorance of the atrocities the Nazis inflicted upon the world. And America was fine with that, because we might need Germany’s support in the growing Cold War. Yeah, it’s pretty clear from the beginning that with Judgment at Nuremberg, Kramer is giving us a pill that’s hard to swallow. But, like all medicine, the bitter taste is worth it.

Judge Dan Haywood (Kramer’s muse, Spencer Tracy) is a recently-retired Maine district court judge who has been made chief judge of the tribunal which will decide the fates of four German judges and prosecutors accused of crimes against humanity for their involvement in the Nazi regime. Haywood is a grandfather and a widower who had only left the country once before, during WWI. He’s come to Nuremberg seeking to understand how something so terrible could have happened, and spends his time out of court meeting locals and attending social events. Nuremberg is still in rough shape, but he sees hope in the little things, like his clerk, Captain Harrison Byers (a pre-Star Trek William Shatner) dating a German girl. Haywood befriends Frau Bertholt (Marlene Dietrich), the woman who used to own the house he is living in and the widow of a general executed by the Allies. They instantly have a deep connection, but, despite having much in common, Haywood struggles with Bertholt’s insistence that she and her husband had no idea about the Holocaust. It becomes clear to Haywood that the Germans want to believe the bad guys are already dead or fugitives and that it’s time to put the war in the rear view mirror.

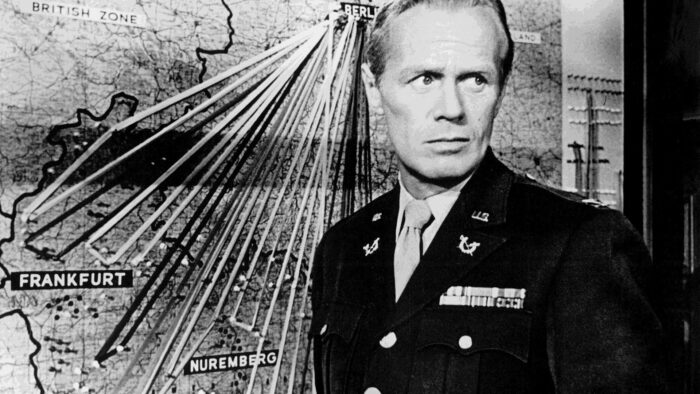

In court, the American prosecutor Col. Tad Lawson (Richard Widmark) passionately attacks the defendants, dredging up all the horrors they had enabled. We eventually find out that Lawson had been involved in liberating one of the concentration camps and, in a particularly memorable scene, he brings footage of the camps as evidence (the graphic footage in the movie was real, shot by American and British soldiers at the end of the war). So Lawson doesn’t care about the Russians or any other public relations nonsense; he wants justice. He’s opposed by Hans Rolfe (Maximilian Schell), an equally brilliant German lawyer, whose defense argues that the defendants never did anything illegal. Rolfe claims that the Russians were even more complicit in enabling Hitler by signing the non-aggression pact in 1939 which allowed Germany to invade Poland and start WWII. He says Americans are equally complicit in crimes against humanity, citing US Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.’s support for the eugenics and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And, of course, one of the defendants, Friedrich Hofstetter (Martin Brandt), claims they had no choice but to execute the laws handed down by Hitler’s government… they were just following orders.

The one exception is defendant Dr. Ernst Janning (Burt Lancaster), who remains stoic while the others plead their cases. Janning was an accomplished and respected legal scholar who, in the name of patriotism, handed down some insane, despicable sentences. Lawson brings in a man (Montgomery Clift) who Janning had ordered sterilized for having a Communist father and, perhaps, having a low IQ. The prosecution also calls Irene Hoffmann (Judy Garland), a key figure in a notorious kangaroo court case that resulted in an innocent Jewish man being executed and Hoffmann imprisoned. Watching Rolfe’s defense echo his life’s greatest shames, Janning eventually insists on testifying himself. In Judgment at Nuremberg‘s best scene, Janning explains just how someone like him could be misled into supporting antisemitic, racist policies despite knowing they were wrong. In stark contrast to his counsel and fellow defendants, Janning argues that all of Germany bears responsibility for the Nazis.

With such an uncomfortable subject and a runtime of over three hours, Judgment at Nuremberg asks a lot of modern audiences to willingly watch it. But if you’re strong enough to try, there’s a lot of meat on these bones. Abby Mann’s script might be too long, but it uses those pages to deal with a lot of weighty issues. If you’re up for a legal epic, it won’t let you down. And Kramer doesn’t shy away from this subject at all, moving his camera around and getting right in his actors’ faces. He even does an early version of The Hunt for Red October language switch trick. And, of course, this cast absolutely feasts on the scenery, chewing it to shreds. Some of them had practice; the movie was adapted from a 1959 TV play as part of CBS’ series Playhouse 90, and Kramer brought many of the German-speaking actors with him.

Judgment at Nuremberg was nominated for 12 Oscars but only took home three: Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Actor (Maximilian Schell—Spencer Tracy was also nominated), and the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award for Stanley Kramer (that’s one of the three lifetime achievement Oscars that are no longer part of the show and are now given by the Academy at the Governors Awards, but in 1962 it would have been part of the main ceremony). Instead, that night was all about West Side Story, which dominated by winning 10 of its 11 nominations — something even Steven Spielberg couldn’t repeat when his remake earned seven nominations but only a single win (Ariana DeBose, who has been fighting for her life to get another good role ever since).

I guess part of the reason I wanted to watch Judgment at Nuremberg was so that I could gauge just how fucked we are. And this was partially reassuring, in a way, because it does show a story of justice triumphing… but only after a period of enormous, unimaginable loss and compromise. It’s also kind of a bummer because there is an undercurrent of everyone really liking Americans, which stings more today than ever before. But mostly what I’ll take away from it is how it shows you’ll never get the satisfaction of bad guys admitting they were wrong. Janning is the closest this movie gets to a repentant villain, but in his last scene, he still begs Haywood to believe him when he says he didn’t know how bad the Nazis would become. Perhaps pride never really does go, even after the fall?