62nd Academy Awards (1990)

Nominations: 1

Wins: 1

I’ve come to the conclusion that Italy is my favorite country when it comes to international cinema. Sorry, Japan. From neorealism to spaghetti westerns to Giallo, there’s a rich tapestry of genres and subgenres that both pay homage to the medium and subvert it. How does Cinema Paradiso fit into this epiphany? Let’s find out.

The film begins in modern-day Rome, where a middle-aged film director, Salvatore Di Vita (Jacques Perrin), is notified by his girlfriend that his mother (whom he hasn’t seen or spoken to in 30 years) called to inform him that a man named Alfredo has died. His girlfriend asks about Alfredo, and Salvatore has a flashback.

Salvatore remembers his youth as a mischievous eight-year-old (Salvatore Cascio) living in a small village in 1945 Sicily. His father has died in the war, his mother (Antonella Attili) constantly swats at him for misbehaving, but he still has DA MOVIES.

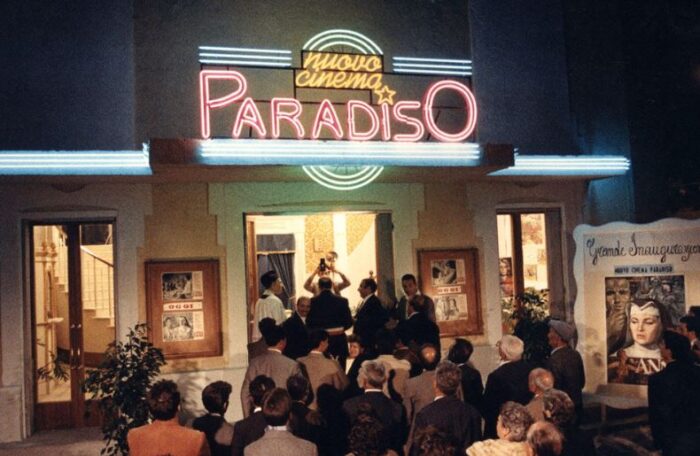

The local theater, “Cinema Paradiso,” is owned by a stodgy priest (Leopoldo Trieste), who has his projectionist, Alfredo (Philippe Noiret), cut out any scenes of kissing. Even with these butchered films, Salvatore is enamored with the magic of cinema. He bugs Alfredo enough to learn how to run the projection booth and steals cut-out frames at every opportunity.

A tragic turn of events comes when a fire breaks out at Cinema Paradiso. Salvatore saves Alfredo’s life, but not before a reel of nitrate film explodes in his face, rendering him blind. A local man rebuilds the theater with his football lottery winnings, and Salvatore becomes the new projectionist, as no one else in town knows the process.

We jump ahead a decade, where a teenaged Salvatore (Marco Leonardo) is still the projectionist at the theater, with drop-ins from Alfredo, who, despite his blindness, still has a keen enough ear to know when the film is projecting out of focus. Salvatore falls for a new girl in town, Elena (Agnese Nano). Despite her father’s disapproval, the two share a whirlwind romance that lasts until Salvatore leaves town to fulfill his compulsory military service.

Salvatore tries to write, but Elena moves on. When Salvatore returns, Alfredo tells him there’s nothing more for him in the town. He urges Salvatore to move on, fulfill his dreams, and cut off contact from the town or any of its residents. He must never give in to nostalgia.

In modern-day, Salvatore returns to the crumbling remains of Cinema Paradiso. He discovers a reel made by Alfredo and projects it onto the screen, revealing all the cut kissing scenes edited into one montage. Salvatore swells with emotion, and the film comes to a close.

Wow! What an ending, bittersweet, but also romantic and powerful. Cinema Paradiso is a film not just about the power cinema has on our emotions, but also about how it brings communities together. Salvatore feels isolated after losing his father, but thanks to the kind tutelage of Alfredo, he finds a proper role model and a passion for art.

Writer/director Giuseppe Tornatore shot the film in his hometown of Bagheria, Sicily, which gives the film an old-school feel. Despite being set mostly in the 40s and 50s, there are never any heavy-handed nods to world events. We simply follow these people and their day-to-day lives, their struggles, their triumphs. It’s a beautiful time capsule.

It would be remiss of me not to mention the film’s sweeping score by Ennio Morricone and his son Andrea. I’ve seen Morricone score action films, thrillers, and horror flicks, but I haven’t seen much of his work in drama. Needless to say, he delivers once again.

The film won the “Best Foreign Language Film” award at the 62nd Academy Awards, and despite being only a modest hit, it helped revitalize Italy’s film industry. Which brings me back to my initial question: “What role does Cinema Paradiso play in my epiphany that Italy is my favorite country for international cinema?”

Cinema Paradiso is a tribute to all those genres I mentioned. It’s an appreciation of the building blocks that formed an industry and the effect cinema has on viewers. I love these Italian films because they feel real, they feel subversive, but also because they are essential to the development of film as a whole. Every country plays its part in preserving history and love while also rebelling against oppression. It’s like all the countries are part of a big quilt that is cinema. Some patches are bigger than others, but all are important.

P.S. Italy’s patch is shaped like a big boot.