Kwaidan is like that film you watch in your Asian Cinema studies class in college. It takes a week to finish and afterward you’re assigned a ten-page paper addressing the theme of guilt in post-WWII Japan as represented in the film’s take on classic Japanese folklore. You read a film analysis book by a dork who sold one screenplay in 1982 (it was never produced), you Google images and examine the lighting and color, you watch and re-watch scenes to appreciate the sense of framing and how they use negative space. At the end of the grueling ordeal, you come to appreciate the film, but you never love it. At least I didn’t. Let’s find out why.

Kwaidan which translates to “Strange Stories” is a 1965 anthology horror film from Masaki Kobayashi, established for his epic The Human Condition trilogy and the samurai classic Harakiri—both in the Criterion collection—Kwaidan is Kobayashi’s most experimental work. Split into four stories detailing classic Japanese morality tales and filmed entirely on sound stages, Kwaidan is like a three-hour surrealist play filled with tales of vengeful ghosts and ancient curses.

The first story, “The Black Hair” is about a samurai who leaves his wife to find a wealthy woman to raise his status. In other words, he’s looking for his sugar mama. The plan works at first until the samurai’s second wife learns of his plan and comes to resent him. The samurai returns to his first wife, promising to help her with his newfound wealth, and they live happily ever after.

Except they don’t. The samurai wakes up the next morning to find his wife has been dead for quite awhile. He abandoned what he had and lost it forever. If this isn’t bad enough, the man starts to age rapidly and is attacked by a strain of evil black hair. Not sure how the hair comes into it but it’s creepy as hell.

The first set piece is the most effective in the film. The story and characters are simple, the plot unfolds in steady deliberate fashion and builds to a terrifying climax. Plus long, evil hair is gross. I like this one.

The second segment, “The Woman of the Snow” is about two men who get lost in the snowy woods cutting wood.The men take refuge in a fisherman’s hut where not long after, the older of the two is killed by a snow spirit in the form of a beautiful woman. The spirit decides to spare the younger man as long as he never mentions what he saw. The young man continues on with his life marrying a beautiful young woman who doesn’t seem to age and starts a family.

Ten years later the couple becomes trapped indoors due to a violent snowstorm. For whatever reason, the young man confesses to his wife that she reminds him a great deal of the snow spirit he saw years ago. The wife transforms to reveal herself as the snow spirit after all these years. Ready to kill the young man, the spirit decides against it because of their children, but tells the young man if he ever mistreats the children in any way, she will return and kill him. The snowstorm ends and she disappears.

The second story takes quite awhile to build to its conclusion, with a significant amount of filler between the man and his blossoming romance. The reveal doesn’t do much to satisfy the setup either. The snow spirit felt like trolling for ten years? And then she doesn’t punish the man after screwing up. It doesn’t make much sense to me and lacks the shock of the first story. Though the winter sets are stunning with painted matte backgrounds of swirling clouds and what look like floating eyeballs in the distance. Still, it’s a difficult one to decipher and it seems to go on forever.

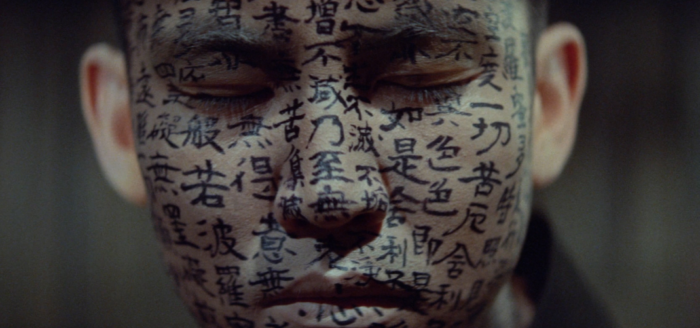

The third story, “Hoichi the Earless”, is a blind musician who sings about the old wars at sea. This war is even visualized in a unique sequence of men on boats again on a bizarre painted set. It’s almost more like you’re watching an experimental stage show than a movie at this point. The musician is called to perform for the royal family but they are unnerved when they think of the possibility that the musician’s songs about dead soldiers could conjure up spirits. In defense, the family paints a Buddhist sutra over the musician’s entire body. They’re safe. At least so they think. Turns out they missed his ears. The ghosts emerge and take the musician’s ears with him.

This one is stunning but cruel. I don’t feel like the musician did anything to deserve the conclusion he received. It’s not like a Twilight Zone where a bad decision leads to an ironic punishment. It’s mean for the sake of mean. That’s not to say it isn’t darkly beautiful. Particularly when the musician is pained in Sanskrit. It’s scary when you think about it afterward but more than anything I found it annoying.

The last story, “In a Cup of Tea” is a writer who sees a strange man in his tea or some bullshit. Honestly, I was having trouble paying attention at this point. Which leads me to my first complaint. This movie is LONG. 182 minutes long. It even has an intermission. Why the stories must be so long I have no idea. I appreciate spending time with the film’s elaborately designed sets but the reveals are never big enough to justify so much build up.

My second issue is I never feel emotionally invested in these characters. They are more of archetypes than real people. I also didn’t mention it earlier but more of the film is told through narration than actual character dialogue. It’s almost like being read to but with visuals. Granted those visuals are incredibly strong they meander due to slow pacing and overabundance of stories.

The film should cut have cut out the last story and trimmed the others to make a tight little visual snack instead of an overstuffed smorgasbord. I simply don’t have the patience to invest that much focus into the story. I appreciate Kwaidan as an art film, as a technical piece of filmmaking, and as a throwback to Japanese folklore, but it’s not accessible. Not for me anyways. Which probably means I’m failing that ten-page paper.